April 30, 2025 | By Sophia Richter | a ten minute read

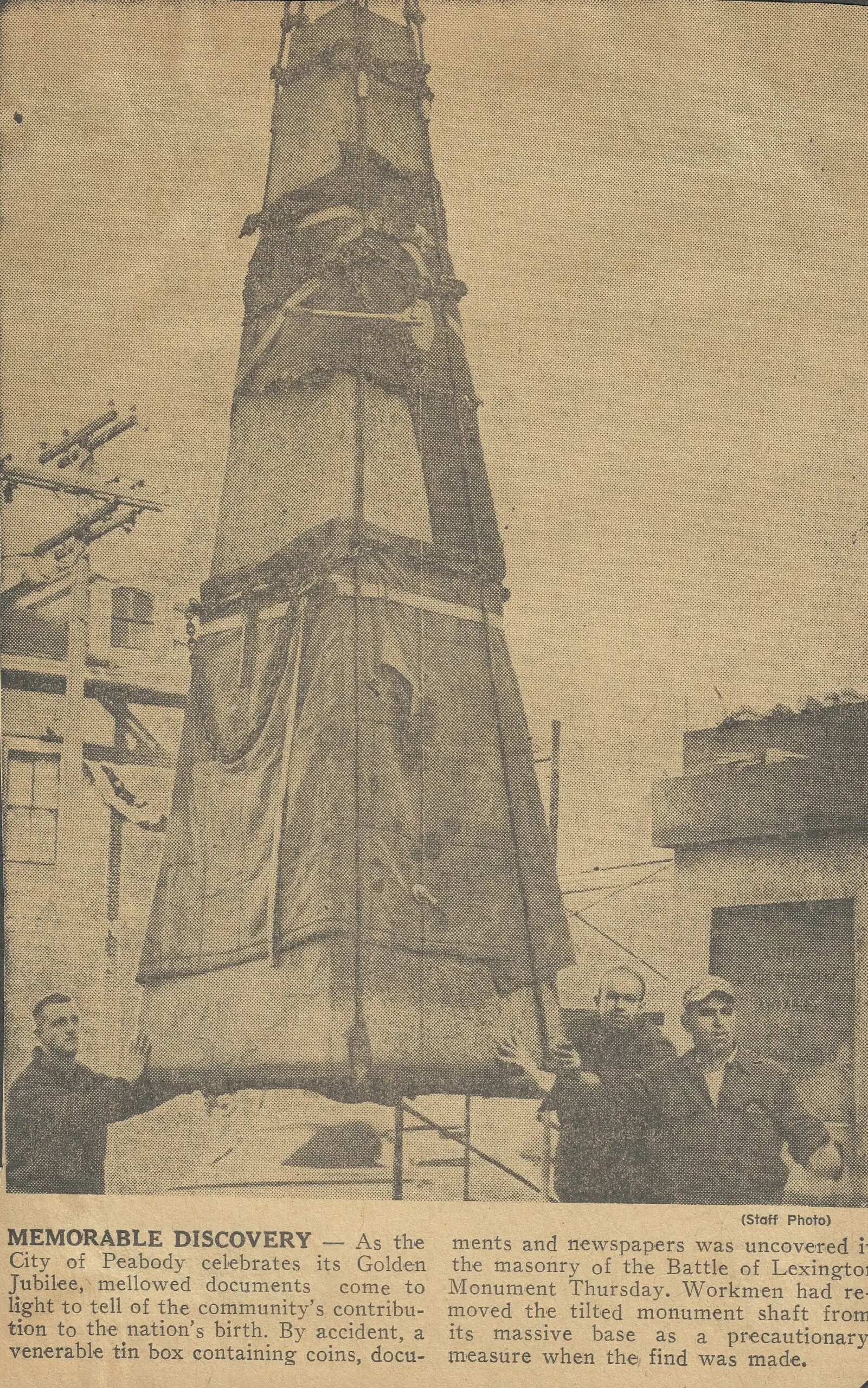

“Memorable Discover,” October 7, 1966.

A week after Patriot’s Day, we explore how the history of the Lexington Monument in Peabody. Join us as we dig into the original sources that suggest what it meant to the people who created it!

There’s Nothing New about Fighting over Monuments

The public debate over monuments has reached almost every town center in America. Whether the subject of concern is Christopher Columbus or a local historically significant figure, Americans are grappling with the meaning behind monuments and whose history is celebrated through them. Some call for wholesale removal of such controversial figures from public spaces. Meanwhile, others seek to add context for how our country interprets the full complexity of their significance.

Whether you treasure, ignore, or detest such monuments, they provoke important questions about our civic and national identity. Who and how we commemorate our history reflects our shared values and the stories that we tell about ourselves.

John Hurley, Removal of portion of the Lexington Monument, August 19, 1985.

Such debates aren’t new. Here in Peabody, a similar conflict emerged over these monumental issues. In 1966, after a severe motor accident involving the Lexington Monument, the City had to decide whether, and where, to remove the monument. This sparked tensions between the municipality and historic preservationists that would continue until 1985. The question was whether the monument would lose its historical significance if moved.

It was during the first removal that a time capsule was found, having been placed in the center of the monument in 1835-36. With these sources, we are able to explore questions about how our understanding of the past has changed and what has remained the same.

Removal Sparks Controversy over Meaning

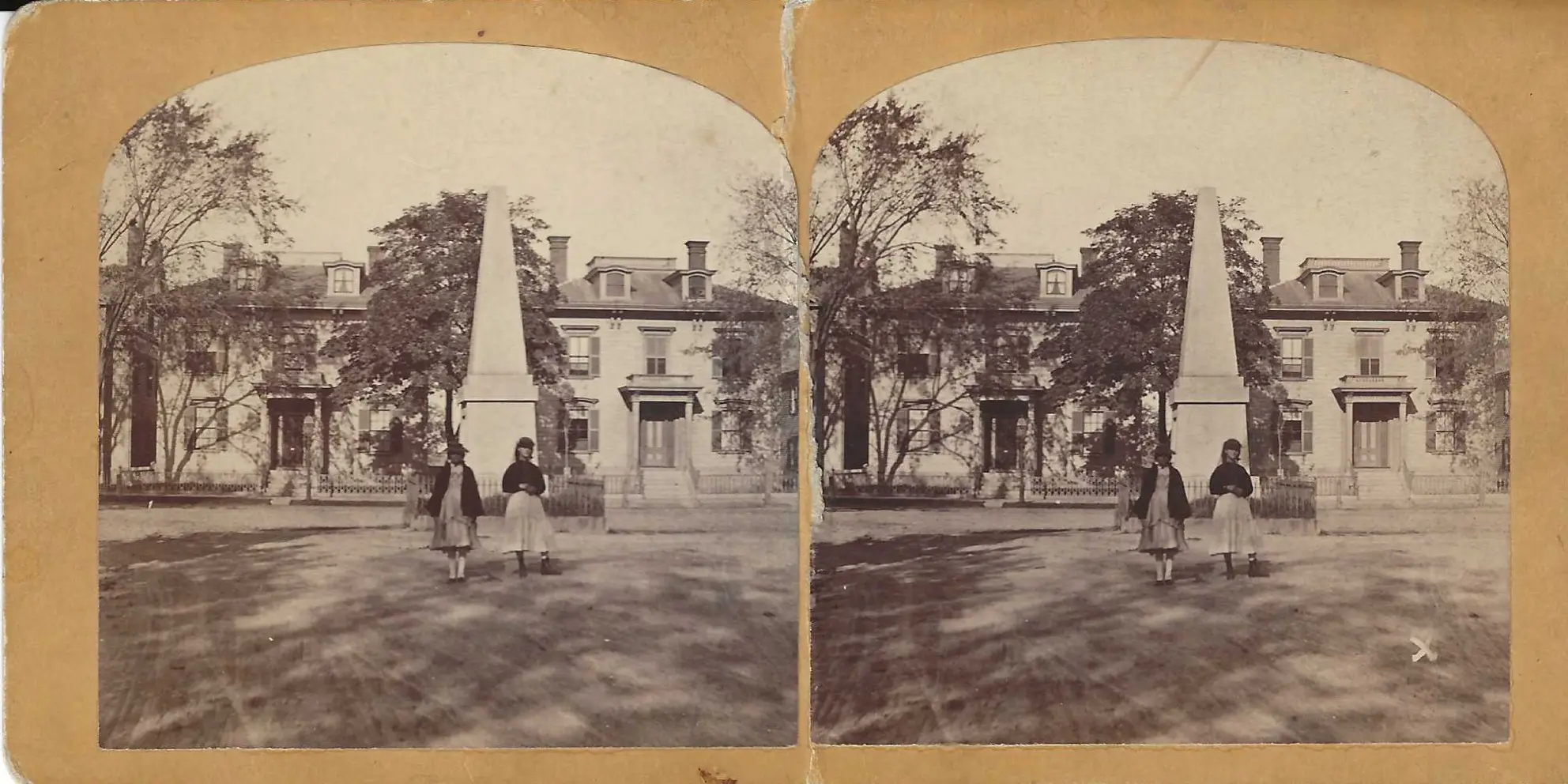

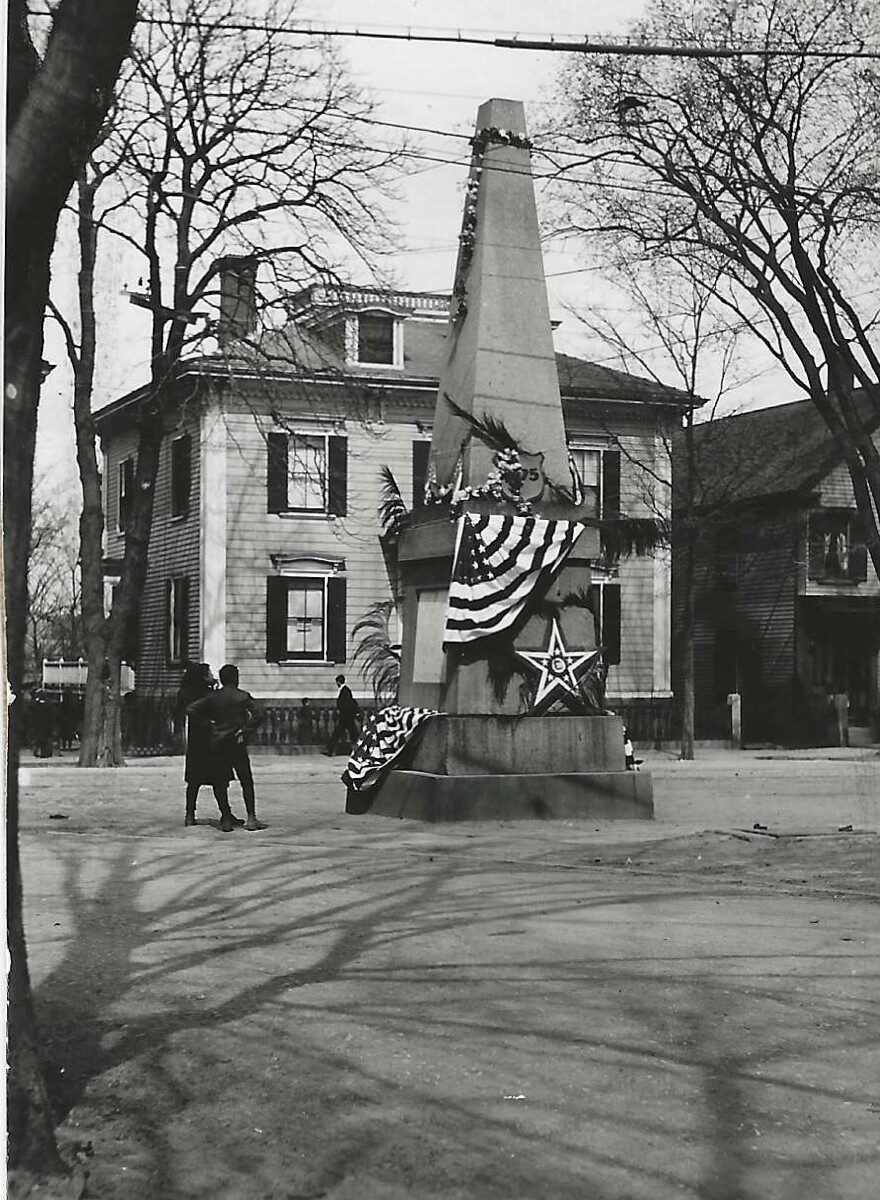

Stereograph of the Lexington Monument, ca. 1880. Peabody Historical Society Archival Collections.

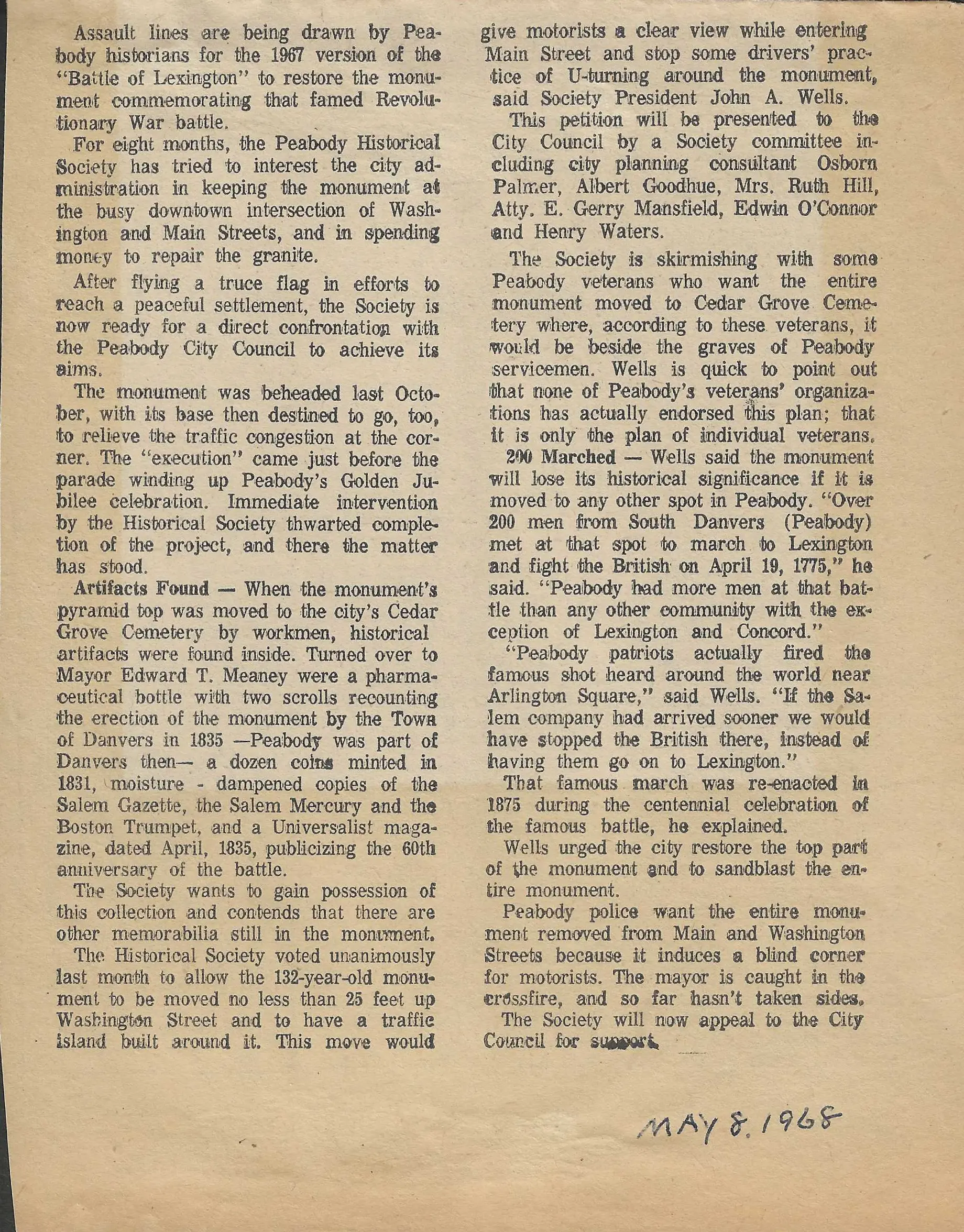

Irving H. Shear, “The Topless Monument,” Peabody Times, May 8, 1968.

1966-1968

As you can see in the stereograph card above, the Lexington monument was initially placed at the intersection of Washington and Main St., right in the middle of the road. After a car accident in October of 1966, the top of the monument was moved to Cedar Grove Cemetery.

For almost two years, the monument sat in its original location without the pyramid. In an effort to have the City address this, the Peabody Historical Society began to advocate on the monument’s behalf. One of the points of conflict was that mayor Meany wanted to remove the monument altogether from the road.

In the end, in 1968, they agreed to move the monument “no less than 25 feet up Washington Street,” putting off mayor Meany’s desire to remove it altogether.

1982-1985

Photograph of the Lexington Monument in 1982, Peabody Historical Society Archival Collections.

The color print you see below was taken in 1982, just before the monument was moved for a second, and last, time to where it stands today.

In June 1982, under mayor Torigian, removal of the Lexington Monument became a topic of debate once again. In an effort to improve traffic flow in downtown Peabody, mayor Torigian had applied for a traffic improvement grant that would include placing traffic lights at this intersection. While Torigian only proposed to nudge the monument out of the intersection, the Peabody Historical Society mounted a defense against this action. This time around, the Society voted against moving the monument.

The Society argued that the monument would lose its historical significance if moved to another site. They pointed out that this location was chosen by Revolutionary War veterans, so “who are we to second-guess their choice?”

For a few years, this was a topic of debate. In May 1983, a protest was held at Bob Bettencourt’s furniture store – where the Bell Tavern now stands – to challenge the City’s effort to move the monument. By August 29, 1985, the City won out and the monument was removed to a site off of Washington Street and out of traffic.

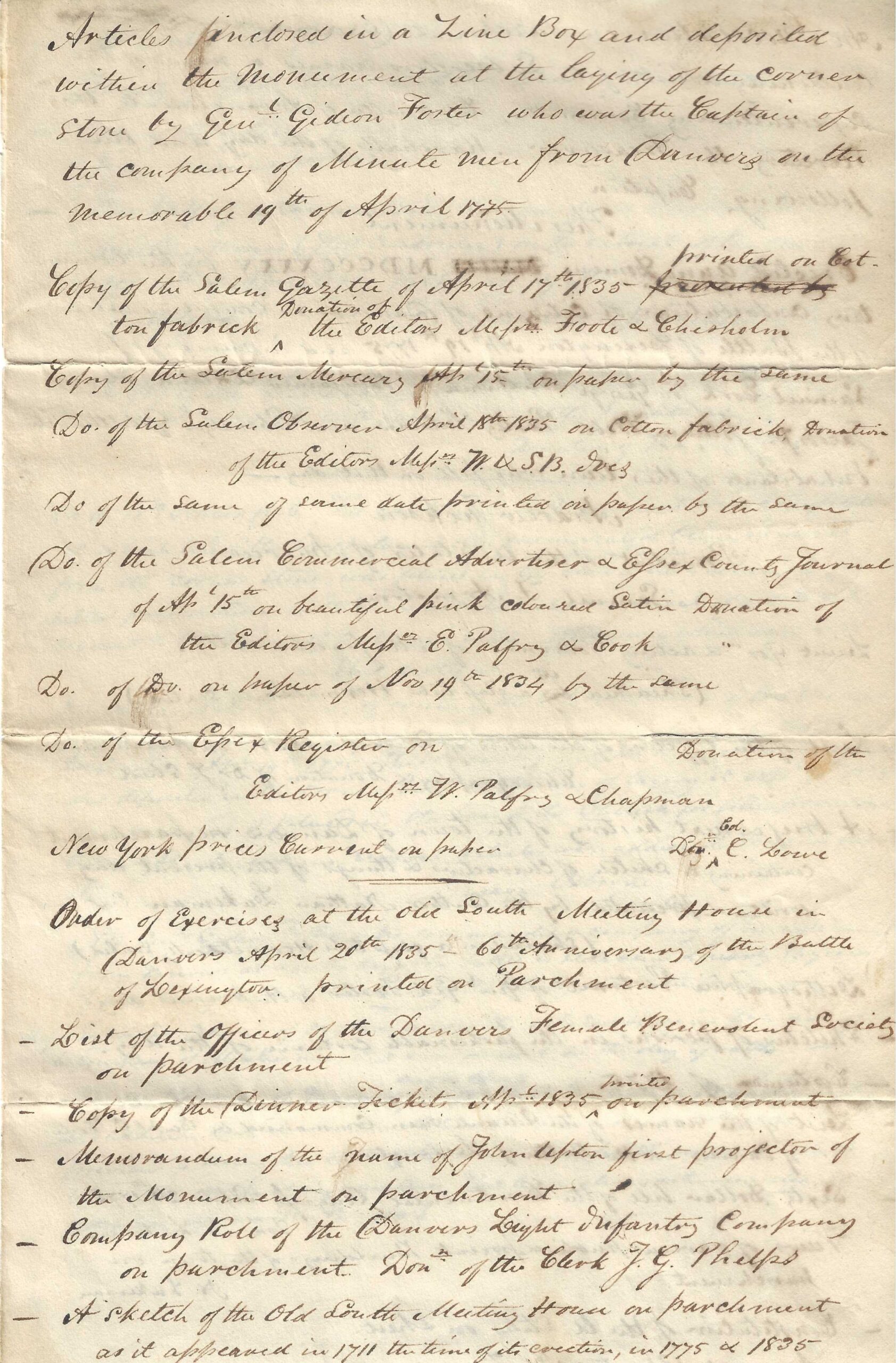

List of items included in the time capsule prepared by the Monument Committee, 1835-1836. Peabody Historical Society Archival Collections.

Did this removal impact the significance of the monument?

Eventually, the majority of the contents of the time capsule would be donated to the Peabody Historical Society, to be shared with the public. The list scrolled in ink, shown here, was written by the Monument Committee of 1835 and included in the time capsule. It indicates what was placed beneath the monument. Included in the list are the original meeting minutes of the Monument Committee.

There is something to be said for why a monument is erected, the context of its creation, to understand what is, in fact, significant about it. These sources help us answer this question!

A Monument by and for the people!

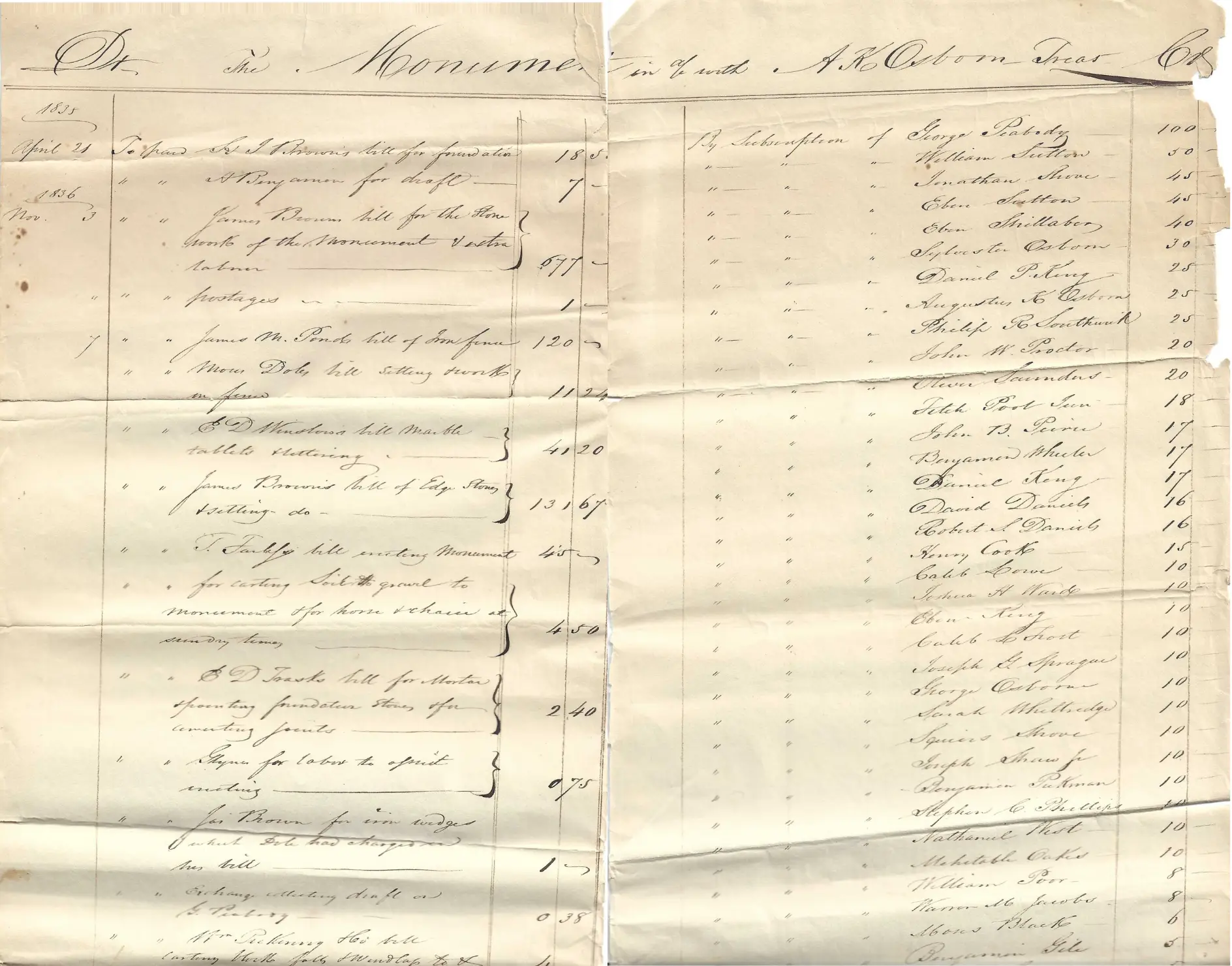

Subscription List, Lexington Monument, 1835. Peabody Historical Society Archival Collections.

Monuments are large, costly, and a collaborative project. The Peabody Lexington Monument is unique in that it was designed and funded entirely by the citizens of the City! Over the course of 1834-35, around 130 individuals, including George Peabody, came together to donate funds, from one dollar to 100 dollars, to the erection of the monument. Of the 130, only two were from outside of Peabody. They came from Salem and Lynnfield.

As the monument was under construction, the Committee of Danvers citizens – then including Peabody – organized the plans for the first Patriot’s Day celebration. Among those members included Caleb Lowe, who was a captain at the Battle of Lexington.

In many ways, the program of events that was voted on by this committee has been replicated up to today. Daniel P. King, esq. was invited to deliver an address on the day that the cornerstone of the monument was to be laid and the Committee agreed to have the “officers and members of the Danvers Light Infantry” perform an escort duty. Flowers and wreaths were placed at the burial sites of the seven Danvers-Peabody men who were killed on April 19, 1775.

Myth and Meaning

The meeting minutes recorded on March 11, 1835, explain why the Monument Committee chose the original location. Compared to the romantic explanation made in the debates of the 1980s, the meeting minutes suggest it was more of a pragmatic decision. For one, Gideon Foster, a decorated military figure who fought on April 19, 1775, did not select the location, nor partake directly in the Committee.

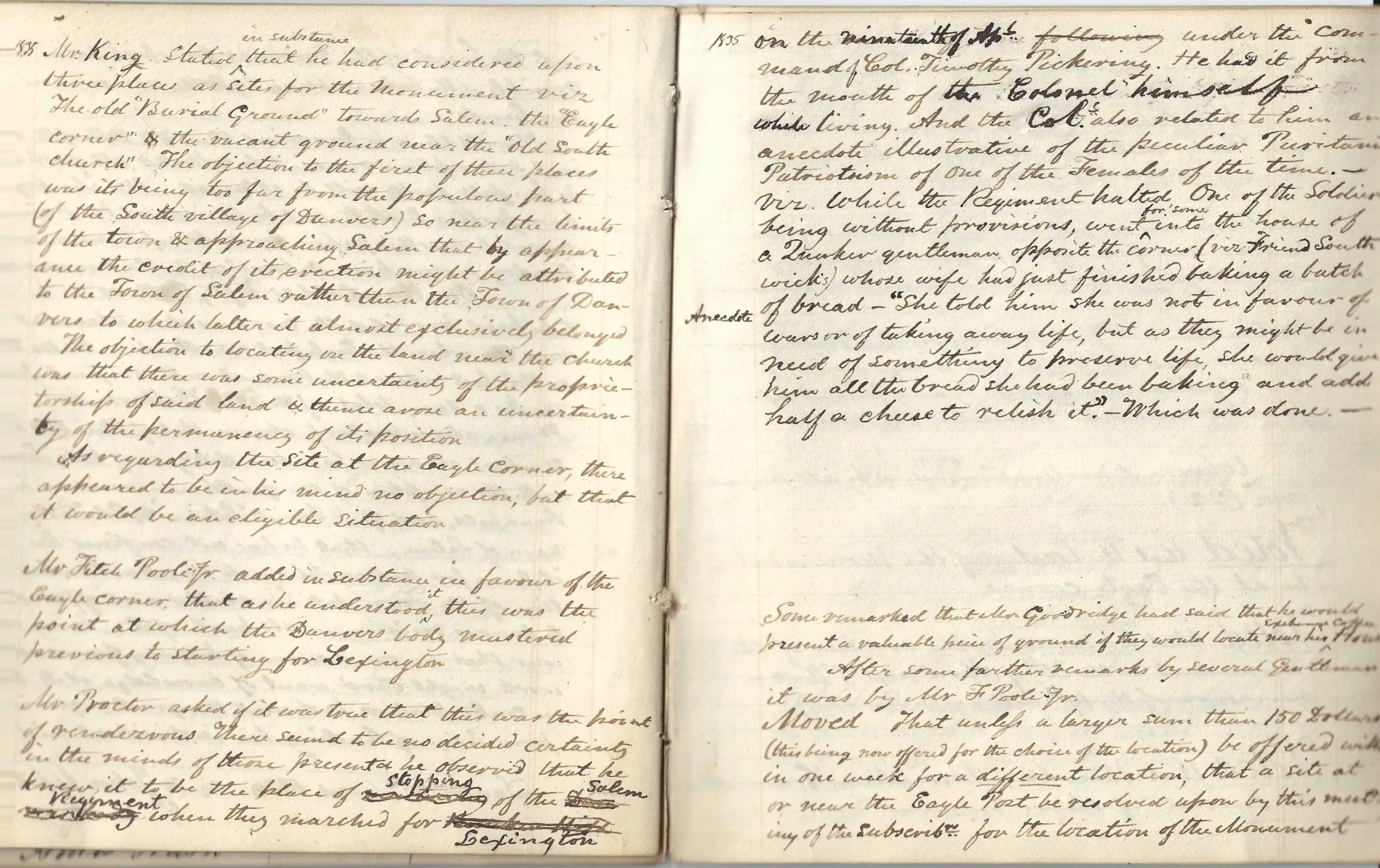

Lexington Monument Meeting Minutes, 1834-1836. Peabody Historical Society Archival Collections.

As you can see, the Committee had proposed a few different sites for the monument. The Committee rejected the Burial Ground because it was so close to Salem as to confuse visitors of its provenance, and they rejected the South Church due to an ownership dispute over the land.

Eagle’s Corner, the corner of Washington and Main St., was not a random option. It did have historical significance to the War, in that Col. Timothy Pickering’s men stopped at the Bell Tavern before marching on to the Battle of Lexington and Concord. Evidently, it is still disputed as to whether this was the “very site” where the Danvers militia gathered before heading to Menotomy. Even so, Eagle’s Corner was not the only viable option in the eyes of the Committee.

More important to the Committee was what the monument was commemorating, not where.

The monument has an inscription, which explains its purpose. This inscription was a source of some tension in 1836. The team of individuals responsible for designing the inscription were divided on what exactly should be said. In a series of open letters, this debate was communicated. From an outsider’s perspective, the difference between the two versions wasn’t very remarkable. And yet, it was through these letters that we can catch a glimpse of why the committee chose to commemorate the Battle of Lexington, as opposed to designing a monument for the Revolution more broadly.

John W. Proctor stated that the Battle of Lexington was not only significant for the entire Revolutionary War, but it was important to Peabody because “it was the day on which we split, the day the first blood was spilt, and at that moment the tie was broken.” Additionally, it was intentional that the inscription does not include commanders’ names.

While another version had suggested including General Gideon Foster, the Committee viewed this as exclusionary, unduly recognizing the patriotism of one, when “all were citizen soldiers […] of which we can make no distinguishing difference.” Not only had there been three companies, and thus three captains, from Danvers that day, but there were almost three hundred soldiers underneath them. Their choice to only name these seven men has an egalitarian tilt to it.

Photograph of the Lexington Monument in 1875. Peabody Historical Society Archival Collections.

Photograph from April 21, 2025, Patriot’s Day in front of the Monument, taken by Cheryl Millard.

The historical significance of the Lexington Monument is apparent from many different directions, least of all the original location where it was erected. Peabody’s history of commemorating the Revolutionary War reminds us that how and what we commemorate our history is a choice that we make. Additionally, monuments that do this commemorating for us are dynamic, their meaning ebbs and flows with time and it is important to check in about the role that they play in our culture.