January 16, 2025 | By Sophia Richter | 10 minute read.

A week after the burial of Jimmy Carter, the 39th president of the United States, and a week before the presidential inauguration of Donald Trump, we invite you to consider how one piece of Peabody history opens the door to a much bigger story that has shaped the politics of our time.

The Leather City left its mark on President Jimmy Carter’s Inauguration Day. In a brick warehouse on Fifth Street, Peabody, Massachusetts, leather workers were pressed for time as they prepared a special product for Jimmy Carter’s inauguration ceremony on January 20, 1977.

Conveyor machine for finishing, Comet Leather Co., (2000.90.1) Leather Collection, George Peabody House Museum.

According to a Daily Peabody Times article, Comet Leather Finishing Co., owned by Theodore Lewalski, was tapped “at the eleventh hour” to process the leather that would be used to bound President Jimmy Carter’s guest books for his inauguration. The final product was “two or three guest books” of blue leather for guests to sign their names at the ceremony.

The article explains that this was not the first “prestige project” that Comet Leather Co. had completed. Lewalski supplied the leather for Boston Mayor Kevin White’s desk top when his office was refurbished the previous year.

And yet, apart from this one article published by the Daily Peabody Times, this patriotic commission went largely unmarked. What was the significance of Jimmy Carter’s election and Inauguration Day to Peabodytes in 1977? Our research team at the Peabody Historical Society dipped into the archives to find out.

1976 in Peabody’s Election History

Ted Lewalski c. 1970’s, (2007.48) Leather Collection, George Peabody House Museum.

In the news article, Ted Lewalski explained that the commissioned work was “kind of a patriotic thing” for him. He said that he was a “Democrat who voted for Carter in the November election”. Lewalski was not alone. Peabodytes overwhelmingly voted for Jimmy Carter in 1976. After four years of inflation, mass job-loss, and the disenchanting politics of Watergate under the Nixon Administration, voters across the country were ready for a change and Jimmy Carter promised to bring it about.

During the beginning of Carter’s administration, the average unemployment rate was just above 7%. Addressing this issue was a top priority for all Americans. Carter had planned to provide “a tax rebate and a public works job expansion program”.

Such debates were taking place in Peabody, as well. The Daily Peabody Times published an opinion piece addressed to “Jimmy” on inauguration day:

“…First, we would hope that your announced mission of bolstering the economy and providing jobs meets with all success. However, success at the expense of renewed inflation would seem to be too high a price to pay. […] Second, we would hope that your glorious honeymoon with the Congress continues long enough to accomplish meaningful progress in human rights and basic needs before the roadblocks of cynicism, partisanship, jealousy, and sectionalism become dominant.”

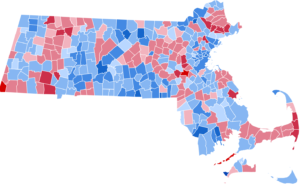

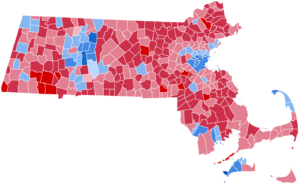

In fact, Peabody has been a Democratic stronghold for a century. Even during elections in which Essex County voted Republican, Peabody stood out. There was only one election between 1928 and 2024 that Peabody voted Republican. It was the year President Ronald Reagan ran for re-election in 1984.

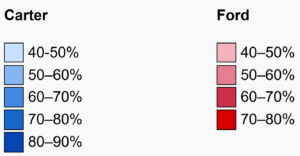

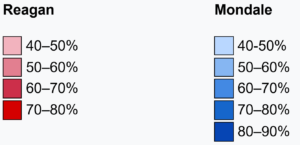

1976 Presidential Election Results

1976 Presidential Election Results  1984 Presidential Election Results

1984 Presidential Election Results

Municipal voter results of 1976 and 1984 Presidential General election. U.S. Census Bureau; Election Results Archive, Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Historians have noted that the shift in voter behavior between Carter and Reagan spoke to wider failures during the 1970s of the political Left to effectively respond to the needs of working-class people in times of economic crisis. In light of the death of President Jimmy Carter, this has been one of the major critiques of his administration and an enduring legacy.

Jimmy Carter, the first New Democrat

While organized labor pushed hard for the election of Jimmy Carter once he was nominated as the Democratic candidate, the Carter administration was not favorable to unions. One of the central tensions between organized labor and the Carter Administration was that Carter perceived powerful labor unions as “special interest lobbies” negatively impacting domestic policy.

From a union perspective, it was Carter’s preference for letting “market forces” decide domestic policy that was the problem.

The AFL-CIO was pushing to raise the minimum wage from $2.30 up to $3 an hour, and automatically index it to annual inflation. The Carter administration disagreed, and wouldn’t go above $2.65 (23 cents below the government’s official poverty line), saying to go higher would damage “business confidence.” Meany called Carter’s number “shameful.”

Not only was inflation an overwhelming problem, but the Carter administration doubled back on New Deal-era approaches to economic reform. Massachusetts Senator Edward Kennedy bemoaned that Carter “left behind the best traditions of the Democratic Party […] We are instructed that the New Deal is old hat and that our best hope is no deal at all.”

Deregulation, business-friendly tax breakings, and trade liberalism (free trade/ globalization) were pillars of his economic platform. While austerity (government cutting budgets to reduce its dept) is widely associated with the Ronald Reagan administration, it began with Carter. Jimmy Carter deregulated many American industries – airlines, trucking, and banking.

Among his other values, Jimmy Carter was the first neoliberal (favoring policies that promote free-market capitalism such as deregulation and reduced government spending) president, laying the foundation for the “New Democrats” (such as Bill Clinton and Barack Obama). Carter’s economic platform contributed to the deindustrialization of U.S. manufacturing during the 1980s. Peabody was among countless industrial towns and cities across the United States that experienced this economic change.

The Leather Industry and Globalization

Ted Lewalski opened his Peabody-based business, Comet Leather Co., in 1965. What was the industry like when he arrived and how did it change leading up to Carter’s election? If Peabody has been such a Democratic stronghold, what did this shifting policy terrain mean for the Tannery City?

“The Sheepskin Factory — Helburn Thompson Co., Salem” painted by Joseph Pechinsky ca. 1950s. Peabody Essex Museum.

At its peak — right before the Great Depression — the leather industry in Peabody employed 8,600 people in 106 tanneries, producing more leather per year than anywhere else in the world. While the leather industry in Peabody would never fully recover from the Great Depression, it would remain stable during the first half of the twentieth century, employing around 5,000 people. This would have accounted for about one out of every six residents of Peabody.

Between the 1930s and the 1960s, many of Peabody’s leather workers were unionized and organized labor was supported by the Peabody City Council, the press, and diverse organizations. And yet, by the 1950’s, the leather industry began to undergo major market shifts that would set Peabody’s industry on a path of decline.

Popular memory about the decline of Peabody’s leather industry fixates on the “harsh environmental laws”, “outsourcing of cheap labor” and the “major leather-worker strike in 1933”. Others contend that there were deeper underlying dynamics at work.

Deindustrialization

After World War II, countries in Asia and Latin America began to restrict their export of raw hides to the United States in order to promote their own tanning industries. This limited the supply of raw materials that companies in Peabody were depended on. At the same time, the cattle ranchers in the United States began to prefer raising their herds for beef as opposed to harvesting calves for hide. This was driven by a rising consumer class of Americans who could afford to buy red meats.

International Fur and Leather Workers Union Conference, Michael O’Keefe (in black suit) and other members of Local No. 21, Leather Industry Collection, Peabody Historical Society & Museum.

Additionally, by the 1950s, the technology used by the leather industry in Peabody was becoming outdated and tannery owners were unwilling or unable to afford modernization. This set Peabody in competition with other regional tanneries from Maine to the Midwest.

Union Local 21 president Michael O’Keefe called for labor reform that could curb the trend of firms moving away to sites of cheaper labor. Among such reforms were trade protections against imported leather shoes, and uniform workmen’s compensation and wage standards across the country. In 1970, O’Keefe wrote that the “U.S. government has failed to face up to new developments in world trade […] with harsh effects on workers and their communities […]. These [developments] include […] the internationalization of technology; the skyrocketing use of investments by U.S. companies in foreign subsidiaries; and the spread of U.S. based multi-national corporations.”

The 1970’s would mark a point of no return for Peabody’s leather industry, not only because of the closures of tannery plants across the city but also because Union Local 21 lost its capacity to be a meaningful force for change. By the late 1980s, “despite aggressive initiatives by Peabody city leaders, the leather industry had relocated to Asian and Latin American locales and left the Leather City behind”.

Thus, by the time Comet Leather Co. got underway, Peabody’s leather industry and its workforce were a fragment of their former selves. Perhaps this was to the Lewalski’s success. Their technology and facilities were more modern than their predecessors. As a finishing company, they were situated at the end of the supply chain, and perhaps less impacted by trade competition in raw materials.

This is conjecture, but I wonder if Ted Lewalski was among the disaffected Democrats who left the party after the Carter Administration. He died in 1983. Perhaps, he was among the last generation to view the Democratic Party as the “working man’s party”. How many people in Peabody felt abandoned by Carter and the Democratic Party? How did Mayor Peter Torigian and Peabody’s local response to deindustrialization compare to the Carter and Reagan’s efforts on the national scale?

Closing reflections

The challenges and key players during the Carter years are strikingly similar to what the Biden and Trump administrations have been facing. The shifts in global politics are challenging U.S. power abroad. We cannot agree on the role of government in regulating global trade and corporate power. High rates of inflation are impacting everyday Americans’ lives. In addition, Carter, Trump, and Biden have grappled with Americans’ deepening distrust of U.S. government and institutions. Carter stated in a speech in July 1979:

Jimmy Carter Inauguration Speech, January 20, 1977. Photo from senate.gov.

“Our people are losing that faith, not only in government itself but in the ability as citizens to serve as the ultimate rulers and shapers of our democracy.”

Peabody Mayor Peter Torigian said something similar in 1980 during his inaugural address: “The turmoil at all levels of government over the last ten years has created a very difficult atmosphere for those in public office. Many times the most sincere efforts are looked upon with suspicion.”

Today as much as during the 1970’s, our suspicions come from a distrust in the balance of power. We are concerned that our government doesn’t have our best interests in mind. We doubt whether our institutions are complex enough, resilient enough, flexible enough.

Perhaps we are so frustrated because we no longer trust the very lens through which we make sense of the world. When I hear the word “polarization”, I think of the politics of our time: small government or big government; regulation or deregulation; free markets or equitable policies; us or them. This was true as much during the middle of the 20th century as it is now.

The politics of our time is shaped by the decisions made during the economic crisis of the 1970s. Austerity and erosion of the New Deal set us on a new course. On January 20, 2025, we will be entering into a new administration. But will we be entering an era of new politics? What norms, what rules, and what values will remain the same and which of these are shifting beneath our feet?

Thank you to Joseph Silva for sharing your insight on this event and to the George Peabody House Museum for providing some of these wonderful photographs from your archival collection.

Terms used in this article:

Inflation – measures how much more expensive a set of goods and services has become over a certain period, usually a year.

Neoliberalism – favoring policies that promote free-market capitalism, deregulation, and reduction in government spending.

Deindustrialization – is the process of a region or country reducing or removing its industrial activity.

Trade liberalism – the process of reducing or removing barriers to trade between countries.

New Democrats – they are seen as culturally liberal on social issues while being moderate or fiscally conservative on economic issues.

Disenchanted – no longer happy, pleased, or satisfied.

Equitable – fair in a way that accounts for and attempts to offset disparities in the way people are treated due to structural inequalities.

Corporate power – extractive corporate behavior that jeopardizes workers, consumers, and broad-based economic growth.

Internationalization – the action or process of bringing a place under the protection or control of two or more nations.

Globalization – growing interdependence of the world’s economies, cultures, and populations, brought about by cross-border trade in goods and services, technology, and flows of investment, people, and information.

What to read more? Interested in our sources?

- “Peabody’s leatherwork will be part of Inauguration,” The Daily Peabody Times, January 15, 1977.

- “Massachusetts Election Statistics: Public Document 43,” Election Results Archive, Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Accessed online: https://electionstats.state.ma.us/

- john a. powell & Stephen Menendian, “Beyond Public/Private: Understanding Excessive Corporate Prerogative,” Kentucky Law Journal Vol. 100 (2011): 83-164.

- Don McIntosh, “Carter Presidency was a Turning Point for Labor,” Northwest Labor Press (January 2, 2025). Accessed online: https://nwlaborpress.org/2025/01/carter-presidency-was-a-turning-point-for-labor/

- Martin Halpern, “Jimmy Carter and the UAW: Failure of an Alliance,” Presidential Studies Quarterly Vol. 26, No. 3 (Summer 1996): 755-777.

- Sean T. Byrnes, “Jimmy Carter Held the Door Open for Neoliberalism,” Jacobin, December 29, 2024.

- Michael Bromberg, “Mr. Carter, ‘Lobbying’ Is Not A Dirty Word,” The New York Times (October 31, 1979) A31.

- James Tobin et al., “The Carter Economics: A Symposium,” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics Vol. 1, No. 1 (1978): 19–45.

- “Carter Discloses Tax Break Plan,” The Daily Peabody Times (January 8, 1977): 1, 14.

- “Jobless Await Carter Employment Plan,” The Daily Peabody Times (January 12, 1977): 1, 5.

- Quoted in William E. Leuchtenburg, In the shadow of FDR: from Harry Truman to Ronald Reagan (rev. edn, Ithaca, NY, 1985), p. 203.

- Phillip J. Cooper, The War Against Regulation: From Jimmy Carter to George W. Bush (University Press of Kansas, 2009)

- Iwan Morgan, “Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and the New Democratic Economics,” The Historical Journal Vol. 47, No. 4 (December 2004)

- Nick French, “Jimmy Carter Worsened the American Malaise He Decried,” Jacobin, December 30, 2024.

- “Common Dedicated to Tannery Workers,” Daily Peabody Times, June 14,1993.

- Lynne Nelson Manion, “Local 21’s Quest for a Moral Economy: Peabody, Massachusetts and its Leather Workers, 1933-1973,” PhD Dissertation, The University of Maine (May 2003).

- Ted Quinn, Images of America: Peabody’s Leather Industry, (Arcadia Publishing, 2008).

- “History of Peabody,” Visit North of Boston, May 23, 2016. Accessed online: https://northofboston.org/blog/history-of-peabody/#:~:text=The%20industry%20began%20to%20decline,throughout%20the%2020th%20century.

- “History. Peabody Leatherworkers Museum,” Peabody Museums. Accessed online: https://peabodymuseums.com/peabody-leatherworkers-museum/history/

- Christina Tree, James Sutton, and John Moynihan, “Leather Through the Ages,” The LeatherManufacturer No. 90 (June 1973).

- “Area Worried About Possible Out of State Migrations,” Leather and Shoes, January 9, 1954, pp. 17- 18.

- Richard O’Keefe, ”New Direction Asked in U.S. Trade Program: LWIU Gears For Union Huddle in Nation’s Capital,” The Bulletin, January, February, March 1970, p. 1.